In 1489, following a visit from the Duke of Calabria, who complained about the state of the fortress and regretted that his garrisons could not be housed there, Ferdinand I of Aragon ordered extension and restoration work, which resulted in an authentic reconstruction of the pre-existing fortified building. Work began in 1490.

Within the framework of the fortified system set up to defend the settlement, the construction of the castle was to complete (with its role as a pole of formal and functional articulation), the defensive system, consisting of the 14th-century walled perimeter and the garrisons placed at crucial points of the settlement itself. On this occasion, the old Norman keep was incorporated into a structure defined by a quadrangular layout, in the corners of which were placed three new towers, oriented according to the cardinal points.

With this reconstruction work, sponsored by the Aragonese central authority, the castle of Corigliano took on its final configuration. The layout of the construction obeyed the requirements of the new techniques of warfare, which required the fortification to be able to absorb artillery hits (2). The author of this work is uncertain, but several elements suggest its attribution to Antonio Marchesi da Settignano, a pupil of Francesco di Giorgio Martini (3). The typological layout of the Corigliano castle is in fact related to other castles built in the same years in the Kingdom of Naples; and those castles have their main formal and technological reference in the renovation work carried out in Naples on the old Angevin castle.

In 1506, the fief of Corigliano and the castle returned to the Sanseverino family. But its state must have been very precarious if the same lord decided to have a new fortified palace built at S. Mauro. In 1516, Antonio Sanseverino re-established his residence in the castle and, in order to increase its security, promoted further renovations.

The construction of the shoes around the base of the corner towers and the building of the Rivellino, placed to protect the only entrance, connected to the castle by two slender drawbridges that guaranteed access to the fortress, probably dates back to this period. As evidence of its new state of efficiency, in 1551 the castle was used as the seat of a military garrison.

In 1616, the fief of Corigliano passed into the hands of the Saluzzo family of Genoa. The new owners, in order to make the castle more suitable for their residence, carried out the first functional adjustments to the fortified structure in 1650. These included the construction of the octagonal tower (placed on the base of the ancient Mastio), the chapel of St. Augustine (which underwent repeated renovations), the new access ramps to the inner courtyard, as well as some rooms for the residence.

In 1720, following the decision to reside permanently in their new palace, the Saluzzo family promoted new renovations to the castle. The need to live in the manor during the summer and autumn periods prompted Agostino Saluzzo to adapt some of the interior rooms of the fortress. In this specific case, some rooms were remodelled and made more comfortable, a balustrade was built outside the throne room and a large stable was built on what is now Via Pometti as part of the castle, replacing the pre-existing one in the moat.

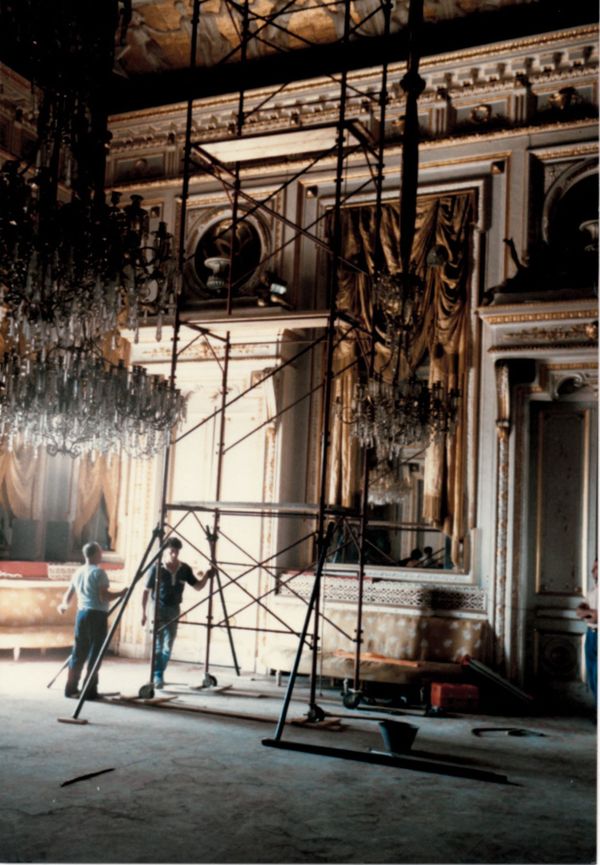

In 1806, the castle was besieged and sacked by French troops. Following these events, the Saluzzo family moved to Naples and decided to alienate the castle and their other property in Corigliano in favour of Giuseppe Compagna of Longobucco. In 1870, Luigi Compagna, Giuseppe's second son, made further changes to the interior of the manor house: the internal corridor was built, reducing the space of the parade ground; the chapel of St. Augustine was frescoed; the upper floor of the Rivellino was demolished to make room for the administration of the House; some rooms were richly decorated.

With the transfer of the last members of the Compagna family to Naples, the historical cycle of the Corigliano castle came to an end.

1) See _ 'Corigliano: history of a town and a territory';

2) In this new cultural and technological climate, the contribution of invention and creativity provided by Francesco di Giorgio Martini, who was involved in the renovation of the castle in Naples, was decisive. Cf., AA.VV. Monumenti d'Italia. I Castelli, Novara, IGDA, 1987, p. 14;

3) Cf. L. De Luca, "Antichità....cit.," in Il serratore, no. 2, 1988;

4) On the typology of the relationship between architecture and its surroundings, cf. AA.VV., L'eredità... cit., p. 100 5) Cf. AA.VV., Monumenti d'Italia. I Castelli, Novara, IGDA, 1987, pag. 170.